When we think about mental health and emotional struggles, the focus is often on the individuals directly experiencing the challenges. Their pain, their stories, and their recovery take centre stage – as they should. However, there is another side to this story, one that is often shrouded in silence. It is the story of those that offer mental health support:

Supporters are the unsung heroes in the mental health journey. They listen. They encourage. They are there to be talked to.

Yet within this diverse group lies a unique distinction: while everyone has the capacity to provide emotional support, trained Mental Health First Aiders (MHFAs) take on a formal and vital role that requires skill, knowledge, and dedication.

Whether you are a supportive friend or a certified first aider, one thing remains true, the burden you carry is often silent yet profound, and the emotional toll on yourself can creep up slowly, almost imperceptibly, until it becomes overwhelming.

When was the last time you considered the well-being of someone supporting you? or your own well-being if you are the one offering support?

Supporters, particularly MHFAs, often feel an unspoken expectation to remain strong, to never falter, and to always be available. This expectation, whether internal or external, can lead to a dangerous pattern of self-neglect.

This post is for them; for you. It is (in my opinion only) an honest look at the challenges faced by anyone who supports others, whether through compassion, friendship, or formal MHFA training.

Here’s the truth: You cannot pour from an empty cup. If you neglect your own needs, you risk burnout, compassion fatigue, and emotional exhaustion, all of which diminish your ability to help others.

In this post I take a moment to shift the focus. This is not about what you can do for others; this is about what you can do for yourself. It is about giving yourself permission to prioritise your own mental health, recognising the warning signs of burnout, and embracing self-care as an essential, not optional, part of being a mental health supporter – whether you are a parent, friend, colleague, or MHFA.

I explore the emotional weight of supporting others, why self-care is not selfish, and practical ways to protect your own mental health while continuing to be there for those who need you. Remember this: caring for yourself is not just an act of self-preservation, it is an act of love for those you are supporting. After all, when you are at your best, you can give your best.

At first glance, the role of a mental health supporter may seem straightforward:

You show up, You listen, You care.

Beneath the surface lies a far more complex and emotionally taxing reality. Supporting someone through mental health challenges means opening yourself up to their pain, holding space for their emotions, and often putting their needs ahead of your own. It is an act of profound compassion, but it can also come at a significant personal cost.

Support (of any kind) is not a one-time event; it is an ongoing process. Whether you are a colleague offering a shoulder to lean on or an MHFA following a structured action plan to assist someone seeking help, the emotional labour of support requires sustained energy and focus. For untrained supporters, this might look like being a constant source of reassurance or encouragement. For qualified MHFAs, it can mean managing their own emotions while calmly navigating someone through a potentially life-altering moment.

This labour is often invisible, especially when the main focus is rightly on the person experiencing distress and/or seeking help. However, it takes a toll on the person offering support, who may carry that emotional weight long after the conversation has ended. Over time, the cumulative effect of being the “go-to” person for someone’s mental health needs can lead to feelings of depletion and even resentment; emotions that are rarely acknowledged due to fear of seeming uncaring.

For all supporters, it is easy to blur the lines between healthy support and overextending yourself.

You may feel obligated to say “yes” to every request, even when it strains your own well-being; this is what makes us human. The unspoken mantra of:

“I’ll rest later – they need me now”

becomes a pattern that chips away at your own mental and physical reserves.

For MHFAs, the boundaries are often more clearly defined through training, but the responsibility of adhering to best practices while being emotionally available can still feel overwhelming. The knowledge that your role is to bridge the gap between immediate support and professional intervention can create pressure, particularly if resources are limited or the person needing help resists further action.

All supporters, especially those with MHFA training, may feel an immense sense of responsibility for the person they are helping. You might question whether you have done enough or worry that your actions, or inactions, could worsen the situation. This sense of responsibility, while rooted in care and compassion, can lead to guilt when outcomes do not improve or when you simply cannot be there for someone all the time.

For untrained supporters, this responsibility is compounded by a lack of training or guidance. You may feel unequipped to handle certain situations, yet still carry the weight of believing it is your job to “fix” the person you care about. The truth is, whether you are an MHFA or an untrained supporter, you cannot solve someone else’s mental health challenges. You can only guide them, encourage them, and ensure they know they are not alone.

Empathy is both a gift and a challenge. For friends, family, and workplace colleagues, empathy often means deeply feeling the emotions of the person you are helping – sometimes to the point of internalising their pain. This phenomenon, known as “empathic distress,” can leave you feeling anxious, helpless, or even traumatised by proxy – aka it can bring about mental health issues to yourself.

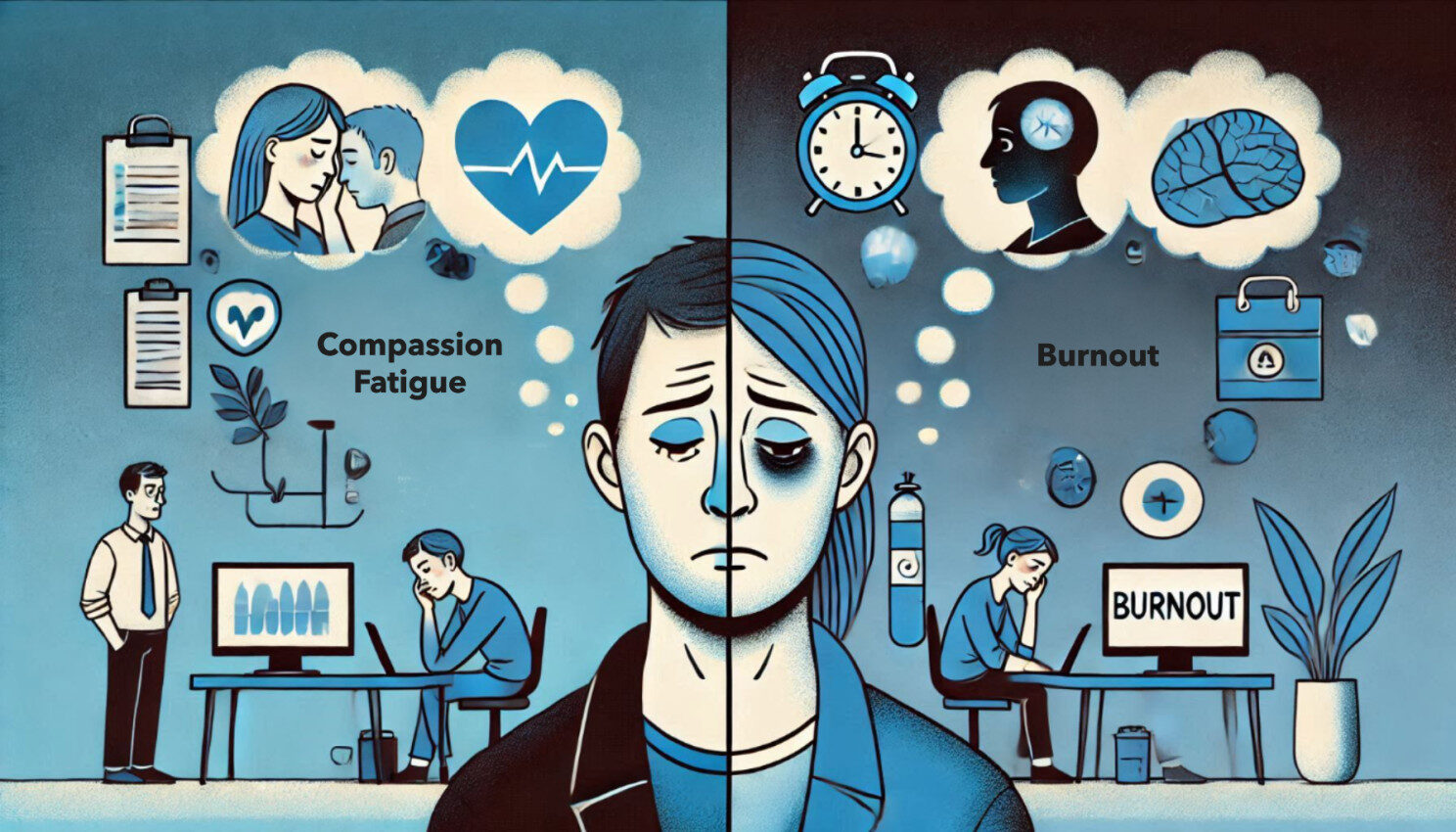

For MHFAs, the challenge of empathy is compounded by the knowledge that you are often called upon during moments of concern or crisis. While training provides tools to manage these situations, it does not shield you from the emotional impact. Witnessing someone’s pain, especially over time, can lead to what is known as “compassion fatigue”; a state of emotional exhaustion that makes it difficult to continue offering support effectively. Compassion fatigue does not mean you care any less; it simply means you have reached your limit.

Supporting someone, whether informally or as an MHFA, can feel isolating. The person you are helping may have access to professional therapy or peer groups, but supporters themselves often lack similar outlets to process their own emotions. For MHFAs, there is sometimes an assumption that the training they’ve received equips them to handle everything on their own. For informal supporters, there may be a fear of burdening others by expressing their own struggles. This isolation compounds the emotional toll, making it harder to seek help when it is needed.

When was the last time you asked yourself how you are feeling? Supporting someone else, whether as a compassionate friend or a trained MHFA, can make it easy to lose sight of your own needs. Recognising the emotional toll of this role is the first step towards finding balance and protecting your own mental health.

Supporting others is a deeply compassionate act. However, it is also an emotionally demanding one. Over time, this responsibility can lead to burnout; an overwhelming state of emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion.

Recognising the signs of burnout is crucial for anyone in a supportive role (in reality burnout can affect anyone in any roll at any time), as it allows you to take action before the toll becomes debilitating.

Burnout rarely arrives with a loud knock. Instead, it creeps in quietly, disguised as “normal” fatigue or stress. MHFAs continually bring this to light as most people dismiss these early warning signs, believing they should be able to handle the pressure. However, burnout builds over time, and if left unaddressed, it can escalate into a state of complete emotional exhaustion and physical breakdown.

For MHFAs themselves, burnout may manifest as feeling overwhelmed by the weight of responsibility, especially after supporting multiple individuals or handling high-stress situations. For most people, it might look like constantly replaying conversations in your head, worrying if you said or did the right thing. Regardless of the role, burnout is a signal that your internal reserves are running dangerously low.

Burnout primarily affects your emotional state, often making you feel:

These emotions are natural responses to prolonged stress, but they can lead to guilt, especially for those in official roles like MHFAs, who often hold themselves to high standards of care.

Burnout does not just affect your mind, it also impacts your body. Some common physical symptoms include:

For MHFAs, the physical demands of being present in high-stakes situations can amplify these symptoms, making it even more important to recognise them early.

Burnout also affects how you think and behave. Some key indicators include:

For untrained supporters, these changes might show up as avoiding phone calls or delaying check-ins. For MHFAs, it could mean hesitating to take on new cases or second-guessing your ability to provide effective support.

It is important to distinguish burnout from compassion fatigue. While the two are closely related, compassion fatigue is specific to the emotional strain of empathising with someone else’s pain. It often manifests as:

Burnout, on the other hand, is more encompassing, affecting all aspects of your mental, emotional, and physical well-being. However, the two often overlap, creating a cycle where compassion fatigue feeds into burnout and vice versa.

Burnout is not a reflection of weakness; it is a natural response to prolonged stress and emotional impact. Recognising the signs early is not just important for your own well-being; it is essential for the person you are supporting. When you are emotionally depleted, it becomes harder to provide the care and presence they need.

If you find yourself resonating with any of these signs, know that you are not alone and that there are steps you can take to recover.

Take a moment to reflect on your own experiences. Do any of these signs feel familiar? Have you been pushing through, believing that “rest can wait” or that your needs are secondary? Recognising these patterns is the first step toward breaking them.

If you have ever felt guilty about taking time for yourself, you are not alone. Many mental health supporters struggle with the idea of self-care. Society has long perpetuated the myth that being selfless is the ultimate virtue; that to truly care for others, you must always put their needs before your own. This narrative is not only harmful but also unsustainable.

Remember this: prioritising your own well-being is not selfish; it is essential.

When you neglect self-care, you risk burnout, compassion fatigue, and emotional exhaustion, all of which diminish your ability to support others effectively. In fact, the most compassionate thing you can do for someone else is to ensure you are mentally and emotionally healthy enough to be there for them.

Self-care is often misrepresented as an indulgence; bubble baths, spa days, or time away from responsibilities. While these activities can be part of self-care, they are not the whole picture. True self-care is about maintaining a balance, setting boundaries, and ensuring your own physical, mental, and emotional well-being journey is essentially realised. Yet for many people, guilt becomes a major barrier to embracing this reality.

To break free from the stigma surrounding self-care, we need to change the way we think about it. Self-care is not a luxury or an escape; it is a responsibility for each of us. Just as you cannot drive a car on an empty tank, you cannot help or assist others effectively when you are running on empty.

For MHFAs, this shift is especially important. The training teaches you how to support others, but it is equally vital to apply those principles to yourself. Just as you would encourage someone else to seek help or take a break, you must allow yourself the same opportunities.

Recognising the importance of self-care is one thing, but overcoming the guilt or stigma associated with it requires actionable steps. Here are a few strategies I hope will help you reframe your perspective:

When you prioritise your own well-being, the positive effects extend far beyond yourself. Your emotional stability, clarity, and energy will ripple out to those you support, creating a healthier and more sustainably dynamic environment. By embracing self-care, you model healthy behaviours for others, showing them that it is okay – and necessary – to put their own mental health first.

When you neglect your own needs in the name of supporting others, you are not truly helping them; you are running the risk of burnout, resentment, and emotional withdrawal. However, when you care for yourself, you are better able to care for them. Take a moment to ask yourself:

What would self-care look like for me today? How can I take one step toward reclaiming my well-being?

Taking care of others is one of the most compassionate and selfless acts a person can perform, but it is not sustainable without taking care of yourself first. Self-care is not one-size-fits-all. It looks different for everyone, but the goal remains the same: to replenish your mental, emotional, and physical reserves so you can continue to show up for the people who need you without sacrificing your own well-being. Below you will see a few practical strategies I have thought about (over the Christmas 2024 festive break), for building and maintaining a self-care routine that may work for you.

Supporting someone through their mental health challenges can stir up a whirlwind of emotions; empathy, frustration, guilt, and even helplessness. Emotional self-care is about acknowledging and processing these feelings rather than suppressing them.

Writing down your thoughts and emotions can help you process difficult situations and gain clarity. Journaling allows you to express your frustrations, fears, and triumphs in a safe space.

Even MHFAs need support. Speaking with a mental health professional can provide a safe space to unload the emotional weight you carry and gain tools for managing stress.

Techniques such as meditation, deep breathing, or even a moment of stillness can help ground you when emotions feel overwhelming. Apps like Headspace or Calm can provide guided meditations tailored for stress relief. I also find “hobbies” can be as important and influential. I have personal preference of listening to a wide range of music on Vinyl records – loud all while I am laying on the floor, eyes closed and just “feeling” the power of music.

A relationship does not have to be the “marriage of your dreams”; it can be with someone special; someone you respect; someone you love; someone you believe is your soul mate and is always there for you; Someone you have yet to meet. My grandma had a saying she would bring forward frequently if I was having personal challenges of my own:

“Some people come into your life for a reason, some come into your life for a season”

In times of difficulties it is the ones that come into your life for a reason (your best friends, soul mates etc.) that are the most important – you may chat to them that often, but they are always there for you (afterthought – why is it they always remember all the crazy stuff you have done together growing up?) On the opposite side of the coin, a seasons length can be 1 week, 1 month, 1 year or longer, but the reality is that when you seek assistance the most, they are the ones who are usually “not available” or cannot help.

Your physical health is deeply interconnected with your mental and emotional well-being. If your body is running on empty, your ability to support others diminishes.

It is believed that MHFAs, often feel isolated in their roles. Connecting with others who understand your experience can help combat feelings of loneliness and provide valuable perspective:

The impact of supporting others can feel overwhelming, especially if you are juggling work, family, and personal commitments. Practical self-care involves finding ways to lighten your load and create space for rest.

As a Mental Health First Aider, your role is unique. While your training equips you to provide immediate support, it is essential to recognise that you are not a therapist or a long-term solution. Acknowledging your limits is a critical part of self-care.

Self-care is not just about reacting to stress; it is about building resilience so you can thrive in the face of challenges. Focus on creating habits that sustain you over time.

Think about your own life: What does self-care look like for you? How can you incorporate even one of these strategies into your daily routine? Remember, self-care is not selfish; it is the foundation that allows you to continue showing up for others.

Even the strongest mental health supporters and most well-trained Mental Health First Aiders (MHFAs) can reach a breaking point. While your focus may always be on helping others, it is essential to recognise when you need help. Seeking support for yourself is not a sign of failure; it is an act of strength and self-awareness. Here I explore how to recognise when you need support and where to turn for help when the emotional burden becomes too heavy.

The first step in seeking help is recognising the signs that you might be struggling. These signs can vary from person to person, but common indicators include:

For MHFAs, these signs may manifest as reluctance to take on new cases, second-guessing your abilities, or feeling emotionally numb during interactions.

Supporters often hesitate to seek help for themselves due to fear of judgment or a sense of guilt. You may think:

“I’m supposed to be the strong one. How can I ask for help when someone else is struggling more?”

The truth is, everyone needs support at times, and reaching out does not diminish your ability to care for others; it enhances it.

When you recognise that you need help, it is important to know where to find it. Here are some options tailored for mental health supporters and MHFAs:

Seeking help is not a one-time act; it is about creating a network of support that you can rely on when needed. Here are some tips for building your own support system:

For MHFAs, ongoing training and professional development can also serve as a form of support. Refresher courses, advanced mental health training, or even supervision sessions can help you feel more confident and equipped in your role. They also provide an opportunity to connect with other first aiders who understand the unique challenges you face.

Take a moment to consider your current state. Are you feeling overwhelmed, isolated, or emotionally drained? If so, what kind of support would help you most right now? Reaching out is not just a way to take care of yourself, it is a step toward becoming a more resilient and effective supporter.

Supporting others, whether as an informal/untrained supporter or a trained Mental Health First Aider (MHFA), is a profound act of compassion and humanity. It is also a role that requires resilience, balance, and an unwavering commitment to your own well-being. Throughout this post, I have explored the hidden burdens of support, the stigma surrounding self-care, and the practical strategies needed to protect your own mental health. Now, it is in your hands to take these insights and turn them into action.

The first step in transforming the way you approach your role as a supporter is acknowledging the emotional weight it carries. It is not a weakness to admit that the responsibility can be overwhelming; it is a strength. By recognising the toll, you empower yourself to take proactive steps toward self-preservation and sustainability.

For MHFAs, this means leaning into the structure and resources provided by your training while honouring your limits. For untrained supporters, it means understanding that your care is meaningful, even if it does not come with formal qualifications. Both roles are vital, and both deserve the same level of care and respect.

The stigma surrounding self-care can be deeply ingrained, but it is one we must challenge and overcome. Self-care is not selfish; it is a foundation for being present, effective, and compassionate in your support for others. Whether it is setting boundaries, seeking professional help, or simply taking a break, self-care ensures you can show up as the best version of yourself.

Remember, it is not just about what you give; it is about how you sustain your ability to give.

When you care for yourself, you model healthy behaviours for those you support, showing them that prioritising mental health is not only acceptable but essential.

No one is meant to bear the weight of support alone. Just as you are there for others, you must allow others to be there for you. Whether it is through therapy, peer support groups, or simply leaning on trusted friends and family, building a strong support system is not a sign of failure, it is a cornerstone of resilience.

For MHFAs, this may also mean tapping into your training networks, seeking supervision, or pursuing further development to bolster your skills and confidence. For untrained supporters, it means recognising that asking for help is a step toward sustaining your ability to help others.

Now that we have explored the challenges and solutions of self-care for supporters, it is time to reflect on what steps you can take today to prioritise your well-being. Consider these questions:

Taking even one small step toward self-care can create a ripple effect, not just in your life but in the lives of those you care about and support.

Imagine pouring from a cup that is perpetually empty. The effort is exhausting, and the results are unsustainable. But when you take time to refill your cup – through rest, self-care, and seeking support – you not only ensure your own well-being but also enhance your capacity to care for others.

Being a mental health supporter is a gift, but it is not one that should come at the expense of your own health. Whether you are a friend, family member, colleague, or MHFA, your mental health matters just as much as the person you are helping. By embracing self-care and building a strong support system, you honour not only yourself but also the people who rely on you.

Take a moment to consider your next step. How will you integrate self-care into your life moving forward? What changes can you make today to ensure you are supporting others in a way that is sustainable and compassionate; not just for them, but for you as well?

As I conclude this post, remember: self-care is not a destination; it is a journey. It is an ongoing commitment to yourself and to those you support. And it starts with one small, intentional act of kindness; for yourself.

Microsoft Solution Architect, Senior Project Manager, and Mental Health Advocate